You can tell a lot about a literary culture by its used bookstores; they are something like the fossil record of a reading public. And one of the things that regularly astonishes me is what you won't find in used bookstores in the United States: contemporary British authors. Nowhere is the old adage ("two countries separated by a common language") more true that in our reading habits. The authors that grace the shortlist for the Man Booker prize hardly make a dent on American literary culture.

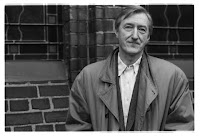

You can tell a lot about a literary culture by its used bookstores; they are something like the fossil record of a reading public. And one of the things that regularly astonishes me is what you won't find in used bookstores in the United States: contemporary British authors. Nowhere is the old adage ("two countries separated by a common language") more true that in our reading habits. The authors that grace the shortlist for the Man Booker prize hardly make a dent on American literary culture. The most egregious omission in this regard has to be Julian Barnes, the best contemporary writer you've never read. I was hooked as soon as I read A History of the World in 10 1/2 Chapters, the book that seemed to earn him a place in the pantheon of supposedly "postmodern" novelists. But Flaubert's Parrot is the book that really sealed my devotion, though his memoir, Nothing to be Frightened Of, is a masterful, honest, even humble meditation on mortality in our secular age.

It's this memoir that comes to mind in Barnes' recent review of Joyce Carol Oates' new memoir, A Widow's Story. Indeed, if the excerpt of JCO's book in the New Yorker is any indication, I'll take Barnes review over Oates' book. His prose is probing without drawing attention to itself--kind of liquid without being soppy. He makes an 18th-century meditation on mourning by Dr. Johnson seem utterly contemporary (and what other critics would have that 1750 essay to hand?). He even has the chutzpah to criticize Oates the widow in the concluding section of his essay, though with grace and sensitivity.

But what's really exquisite about the essay is how perfectly Flaubertian it is: in the best spirit of the master, Barnes observes the discipline of self-suppression--achieving that vaunted Flaubertian ideal of objectivity that prevents him from even appearing in the essay. The "I" here is not flaunted, to that point that the reader might not realize or recall that Barnes' own widowhood is still quite fresh (following the death of his wife, Pat Kavanagh). But while Barnes the widower--that Barnesian "I"--does not parade itself in the essay, of course it impresses itself on the entire piece. Barnes' the widower is everywhere between the lines, informing an entire sensibility, resonating with Oates' clichéd mourning ("what is grief at times," he asks, "but a car crash of cliché?). And it is the sympathy of widowhood that also gives him license to criticize Oates' silence about her prompt remarriage. In the age of the confessional, solipsistic memoir, Barnes' Flaubertian discipline is to be admired.