Two pieces for reflection: (1) the Archbishop of Canterbury's recent op-ed for The Times on the repercussions of American foreign policy for Christians in the middle east; and (2) Pope Benedict's Christmas message.

Come quickly, Prince of Peace.

Sunday, December 24, 2006

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Auden: A "Boxing Day" Selection

On the last day of term I read this selection from W.H. Auden to my class. It is more properly what in Canada (or the UK) we would call a "Boxing Day" poem--an apres-Christmas reflection. But I'll be away from my computer on Boxing Day, so thought I'd share it now:

Well, so that is that. Now we must dismantle the tree,-W.H. Auden (from For the Time Being)

Putting the decorations back into their cardboard boxes --

Some have got broken -- and carrying them up to the attic.

The holly and the mistletoe must be taken down and burnt,

And the children got ready for school. There are enough

Left-overs to do, warmed-up, for the rest of the week --

Not that we have much appetite, having drunk such a lot,

Stayed up so late, attempted -- quite unsuccessfully --

To love all of our relatives, and in general

Grossly overestimated our powers. Once again

As in previous years we have seen the actual Vision and failed

To do more than entertain it as an agreeable

Possibility, once again we have sent Him away,

Begging though to remain His disobedient servant,

The promising child who cannot keep His word for long.

The Christmas Feast is already a fading memory,

And already the mind begins to be vaguely aware

Of an unpleasant whiff of apprehension at the thought

Of Lent and Good Friday which cannot, after all, now

Be very far off. But, for the time being, here we all are,

Back in the moderate Aristotelian city

Of darning and the Eight-Fifteen, where Euclid's geometry

And Newton's mechanics would account for our experience,

And the kitchen table exists because I scrub it.

It seems to have shrunk during the holidays. The streets

Are much narrower than we remembered; we had forgotten

The office was as depressing as this. To those who have seen

The Child, however dimly, however incredulously,

The Time Being is, in a sense, the most trying time of all.

For the innocent children who whispered so excitedly

Outside the locked door where they knew the presents to be

Grew up when it opened. Now, recollecting that moment

We can repress the joy, but the guilt remains conscious;

Remembering the stable where for once in our lives

Everything became a You and nothing was an It.

And craving the sensation but ignoring the cause,

We look round for something, no matter what, to inhibit

Our self-reflection, and the obvious thing for that purpose

Would be some great suffering. So, once we have met the Son,

We are tempted ever after to pray to the Father;

"Lead us into temptation and evil for our sake."

They will come, all right, don't worry; probably in a form

That we do not expect, and certainly with a force

More dreadful than we can imagine. In the meantime

There are bills to be paid, machines to keep in repair,

Irregular verbs to learn, the Time Being to redeem

From insignificance. The happy morning is over,

The night of agony still to come; the time is noon:

When the Spirit must practice his scales of rejoicing

Without even a hostile audience, and the Soul endure

A silence that is neither for nor against her faith

That God's Will will be done, That, in spite of her prayers,

God will cheat no one, not even the world of its triumph.

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Where's the World's Wealth?

The World Institute for Development Economics Research has just released a new study on "The World Distribution of Household Wealth." Unlike the measure of "income," the measure of "wealth" considers household assets and resources. According to the findings of the study, "the richest 1% of adults alone owned 40% of global assets in the year 2000, and that the richest 10% of adults accounted for 85% of the world total. In contrast, the bottom half of the world adult population owned barely 1% of global wealth." (The .pdf version of the report is a rich resource.) Consider the following graphical depictions of just a couple elements:

Thursday, December 07, 2006

Who "Supports Our Troops?"

My oldest son and I listened with rapt attention to a recent NPR report on the persecution of soldiers returning from Iraq with Post-Traumatic Stree Disorder (PTSD). Definitely worth a listen (or a read: the transcripts are online--but I would recommend listening). The report is riveting, heart-breaking and angering all at the same time. The human cost of this war is staggering, and it is remarkable how the administration and the military itself is failing to support our troops.

Wednesday, November 29, 2006

The Pope in Turkey

Since arriving in Turkey, the Pope has described Islam as a "religion of peace" and stated that Turkey should be admitted into the European union? I can't way to see what Fr. Neuhaus, George Weigel and the National Review are going to do with those claims.

Friday, November 24, 2006

Scientism Evangelistic Rally

A recent article in the New York Times provides a fascinating peek inside what could only be described as an evangelistic planning rally for scientism--the religion of Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, and their ilk. Very entertaining reading, especially for anyone who has ever attended an evangelistic crusade (that is, about 1.2% of NYT readers!).

But the article is also disheartening: is there any hope of people actually talking to one another in our polarized culture? Or are we doomed to live in tribalistic quadrants carved up by the polemic of talk radio, cynically preaching to our respective choirs?

But the article is also disheartening: is there any hope of people actually talking to one another in our polarized culture? Or are we doomed to live in tribalistic quadrants carved up by the polemic of talk radio, cynically preaching to our respective choirs?

Monday, November 13, 2006

Postcard from Belgium

I just returned from a fabulous conference at the Katholieke Universiteit in Leuven, Belgium on "Augustine and Postmodernism: A New Alliance Against Modernity?" (9-11 November), hosted by Lieven Boeve and Tom Jacobs--who did a wonderful job both pulling together a stimulating team of scholars for this colloquium, and then providing unparalleled hospitality that nourished our conversations. Here are just a few pictures and reflections.

Leuven, a late medieval city in the Flemish part of Belgium, is a very short train ride from Brussels. The Katholieke Universiteit (Catholic University)--is a core feature of the town and students are everywhere. It is very much a "university city" and given its size and history, it reminded me of Cambridge in many ways. Pictured here is the famous Town Hall of Leuven, a quintessentially Gothic structure completed in 1468.

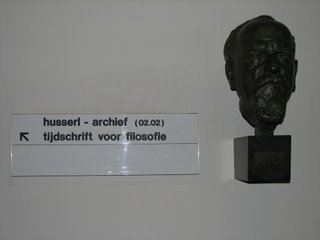

Leuven's Faculties of Theology and Philosophy are internationally esteemed. The theology

faculty made a mark on Vatican II (indeed, some of the conversations at our conference circled back to consider just what was at stake at the council and what it would mean to continue--or contest--that legacy) and has continued to generate important work, including recent engagements with postmodernity. The Institute of Philosophy is home to the Husserl Archives and has for decades been one of the premier influences on contemporary phenomenology. So it was a treat for me to make a bit of a 'pilgrimmage' to the Husserl Archives while I was there.

faculty made a mark on Vatican II (indeed, some of the conversations at our conference circled back to consider just what was at stake at the council and what it would mean to continue--or contest--that legacy) and has continued to generate important work, including recent engagements with postmodernity. The Institute of Philosophy is home to the Husserl Archives and has for decades been one of the premier influences on contemporary phenomenology. So it was a treat for me to make a bit of a 'pilgrimmage' to the Husserl Archives while I was there.An unanticipated treat was Belgian cuisine. Our hosts showed us a wonderful time in local establishments. While I came with high expectations for Belgian beer (I learned that Stella Artois constitutes the dregs of Belgian beer that they send to us in the America, saving the best stuff for themselves!), I enjoyed several excellent dining experiences. These included a tantalizing pork dish (covered with Danish blue cheese) on Friday night, followed with a Saturday lunch of steak, peppercorn cream sauce, frites (which the Belgians, not the French, invented!), and a glass of Duvel. This was topped off when I visited some new friends, the Micheners, on Saturday in the Wallonie (French-speaking) region of Belgium (just south of Leuven). There I enjoyed "raclette," which is both a kind of cheese and a mode of preparation: cheeses, meats, and vegetables prepared in a central table-top grill, then poured over Belgian potatoes and complemented by French wine. Yeah, the airline food the next day was, er, a bit of a step down from all that!

The conference conversation--focused on the role that Augustine plays (should play, could play) in contemporary theology and, in particular, theological accounts of cultural engagement--was top-notch and stimulating. The conference was organized as what they described as an "expert colloquium"--a sort of closed-door roundtable discussion with a few folks listening in. Some of the other speakers including two of my former teachers (Robert Dodaro from the Augustinianum in Rome and Anthony Godzieba from Villanova) as well as folks like Fergus Kerr and Emmanuel Falque (from the Institut Catholique in Paris), and several very sharp younger scholars (including Holger Zaborowski). The proceedings of the conference will be published next year. But most importantly, the conversation--at times animated--really helped me to crystallize some of the key issues I need to think about as I'm trying to develop an Augustinian political phenomenology.

One of the other delights of being in Belgium was getting to know the good folks at the Evangelical Theological Faculty on the south side of Leuven. Having briefly met Ron Michener once before, I enjoyed a morning of conversation with Ron, Patrick Nullens, Filip Cavel, and a couple of other doctoral students about the challenges and opportunities for evangelical theology in Europe.

Thursday, November 09, 2006

God's Politics?

I don't mean to keep flogging the same horse, but man I find Jim Wallis frustrating! A couple of recent occasions for new ire:

1. On the flight over to Belgium, I caught up listening to some of Krista Tippett's Speaking of Faith podcasts, including a conversation with former Republican Senator and Episcopal priest, John Danforth on "Conservative Politics and Moderate Religion" (I think I would prefer moderate politics and conservative religion, but don't hold me to that). Danforth has been shilling his new book Faith and Politics in which he seems to conclude that if someone takes a "position" on something, and claims that it is God's position on something, then one is being "divisive"--and being divisive seems to be the cardinal sin for Danforth. If one quips that Jesus was pretty decisive, I'm guessing that Danforth would say 'that's different' because Jesus was God (though he's an Episcopalian priest, so I can't say for sure). In any case, while I'm all for humility (and goodness knows we need more of it in public discourse [and I am the chief of sinners]), such castigations of "divisiveness" strike me as, in fact, false humility--which doesn't help anyone. Danforth is just a popularized version of John Rawls. (While I'm a bit hesitant to make the link, because of guilt by association, intellectual honesty compels me to note that Ramesh Ponnuru's review of Danforth's book in the National Review gets this point right.)

But Danforth's wishy-washy-ness helped to highlight (again) how much Jim Wallis is playing the same game as the Religious Right--they just disagree about specifics. While Wallis is as critical of the Religious Right as anyone--and the Right is clearly the target of Danforth's book--anyone who writes a book entitled God's Politics is working with the same tools. Wallis' constantianism of the left is (or should be) just as much a target of Danforth's critique as Dobson and Falwell.

2. And now, after the Democrat's (seeming) sweep of the mid-term elections, Jim Wallis is claiming that it was the Christian left who were the deciding factor in giving the Dems victory (see also Christianity Today's nice online piece, "Declaring Victory"). Wallis is still jealous, I guess, about all the press's causal claims about the role of the Religious Right in '04. But this evokes a couples responses.

First: Really? But is there any data to support this claim? Exit poll questions were asking this? Methinks there's some serious over-estimation going on here, tied to a certain over-estimation of Wallis' own importance.

Second, there is a remarkable irony about Wallis' posturing. At one point Wallis says this: "When Democrats can run authentically as persons of faith, they can beat back the idolatrous claims of the Religious Right that God is only on their side." This from a guy who has the audacity to write a book called God's Politics. I think the "only" in this quote is superfluous, and masks the fact that Wallis thinks that God is on his side.

1. On the flight over to Belgium, I caught up listening to some of Krista Tippett's Speaking of Faith podcasts, including a conversation with former Republican Senator and Episcopal priest, John Danforth on "Conservative Politics and Moderate Religion" (I think I would prefer moderate politics and conservative religion, but don't hold me to that). Danforth has been shilling his new book Faith and Politics in which he seems to conclude that if someone takes a "position" on something, and claims that it is God's position on something, then one is being "divisive"--and being divisive seems to be the cardinal sin for Danforth. If one quips that Jesus was pretty decisive, I'm guessing that Danforth would say 'that's different' because Jesus was God (though he's an Episcopalian priest, so I can't say for sure). In any case, while I'm all for humility (and goodness knows we need more of it in public discourse [and I am the chief of sinners]), such castigations of "divisiveness" strike me as, in fact, false humility--which doesn't help anyone. Danforth is just a popularized version of John Rawls. (While I'm a bit hesitant to make the link, because of guilt by association, intellectual honesty compels me to note that Ramesh Ponnuru's review of Danforth's book in the National Review gets this point right.)

But Danforth's wishy-washy-ness helped to highlight (again) how much Jim Wallis is playing the same game as the Religious Right--they just disagree about specifics. While Wallis is as critical of the Religious Right as anyone--and the Right is clearly the target of Danforth's book--anyone who writes a book entitled God's Politics is working with the same tools. Wallis' constantianism of the left is (or should be) just as much a target of Danforth's critique as Dobson and Falwell.

2. And now, after the Democrat's (seeming) sweep of the mid-term elections, Jim Wallis is claiming that it was the Christian left who were the deciding factor in giving the Dems victory (see also Christianity Today's nice online piece, "Declaring Victory"). Wallis is still jealous, I guess, about all the press's causal claims about the role of the Religious Right in '04. But this evokes a couples responses.

First: Really? But is there any data to support this claim? Exit poll questions were asking this? Methinks there's some serious over-estimation going on here, tied to a certain over-estimation of Wallis' own importance.

Second, there is a remarkable irony about Wallis' posturing. At one point Wallis says this: "When Democrats can run authentically as persons of faith, they can beat back the idolatrous claims of the Religious Right that God is only on their side." This from a guy who has the audacity to write a book called God's Politics. I think the "only" in this quote is superfluous, and masks the fact that Wallis thinks that God is on his side.

Saturday, November 04, 2006

Praying for Ted

This morning, while trying to undo autumn's leafy deposits across the backyard, I found myself--much to my surprise--praying for Ted Haggard. To be sure, Haggard represents almost everything I loathe about the Religious Right and the Babylonian captivity of evangelicalism (captured so well in Jeff Sharlet's Harper's piece a while back). And news of these allegations has made leftist bloggers just downright giddy.

But it's curious how this explosion in Haggard's life could be a reminder that, despite our political differences, Ted Haggard is still a brother. (And maybe this is a tiny little confirmation that, despite all my protests to the contrary, I'm still an evangelical.) Recent video of Haggard in his SUV, with his wife in the passenger seat, was one of the most painful snippets I've seen in a while. Forced to revise his story (I think common sense should tell us to expect further revisions), Haggard's tired eyes keep darting to his wife's face as he has to confess to compromises and failures (the camera's gaze is almost merciful in not showing her face).

While sociologists are constantly looking for the defining features of "evangelicals," I wonder if the Haggard case might provide a more visceral criterion: if you see what Haggard and his family are going through, and are moved to consider their pain, and have a haunting but persistent sense that "there, but for the grace of God go I"--then you're an evangelical. Evangelicals in their best moments are painfully aware of the brokenness of our world, and of our very selves--even our redeemed selves. And thus struggle to answer the Spirit's call to "weep with those who weep" (Rom. 12:15).

"Let him who thinks he stands take heed lest he fall" (1 Cor. 10:12).

But it's curious how this explosion in Haggard's life could be a reminder that, despite our political differences, Ted Haggard is still a brother. (And maybe this is a tiny little confirmation that, despite all my protests to the contrary, I'm still an evangelical.) Recent video of Haggard in his SUV, with his wife in the passenger seat, was one of the most painful snippets I've seen in a while. Forced to revise his story (I think common sense should tell us to expect further revisions), Haggard's tired eyes keep darting to his wife's face as he has to confess to compromises and failures (the camera's gaze is almost merciful in not showing her face).

While sociologists are constantly looking for the defining features of "evangelicals," I wonder if the Haggard case might provide a more visceral criterion: if you see what Haggard and his family are going through, and are moved to consider their pain, and have a haunting but persistent sense that "there, but for the grace of God go I"--then you're an evangelical. Evangelicals in their best moments are painfully aware of the brokenness of our world, and of our very selves--even our redeemed selves. And thus struggle to answer the Spirit's call to "weep with those who weep" (Rom. 12:15).

"Let him who thinks he stands take heed lest he fall" (1 Cor. 10:12).

Thursday, November 02, 2006

A Miscellany

Just a few recent pieces of note that others may find of interest:

- A wonderful essay by Alasdair MacIntrye: "The End of Education: The Fragmentation of the American University" over at Commonweal (HT: Jeff Bouman)

- Martin Marty on "theocracy" in Sightings

- Brian Leiter, with whom I'm not often prone to agree, has an interesting post on "Why I am Not a Liberal"

- A downright spooky article about "extreme" evangelist Stephen Baldwin (yes, he's one of those Baldwins)

Monday, October 16, 2006

The Lonely Commute

Last spring I taught a seminar on "Urban Altruism" that explored the material conditions of community--how aspects of urban planning, architecture, and other social arrangements either foster or detract from community-building (friendships, civic concern, neighbor-love, etc.). Two recent reports confirm much of what we discussed in the class:

1. This past summer the American Sociological Review published a landmark study on "Social Isolation in America" (pdf). Over a twenty year period, the study considers the change in the circle of close friends ("confidants") that Americans have. Over the 20-year span these social networks decreased by 1/3. This might be at least partially be explained by a report unveiled this week...

2. The Transportation Research Board released the third edition of its report, Commuting in America. The report indicates that the lonely commute has gotten even lonlier: as more commuting traffics from suburb to suburb (rather than suburb to core city), the number of new solo drivers grew by almost 13 million from 1990 to 2000. The report also indicates that the number of workers with commutes over 60 minutes grew by 50 percent (!), and that more Americans are leaving for work between 5:00-6:30am.

Pretty hard to cultivate significant friendships when we're spending so much time by ourselves in our cars. Instead, we have more and more people listening to the inanity of talk radio in America. Someone needs to do a study that consider the correlation between increased solo commuting, the explosion of talk radio, and the increased polarization of American "civic" discourse.

1. This past summer the American Sociological Review published a landmark study on "Social Isolation in America" (pdf). Over a twenty year period, the study considers the change in the circle of close friends ("confidants") that Americans have. Over the 20-year span these social networks decreased by 1/3. This might be at least partially be explained by a report unveiled this week...

2. The Transportation Research Board released the third edition of its report, Commuting in America. The report indicates that the lonely commute has gotten even lonlier: as more commuting traffics from suburb to suburb (rather than suburb to core city), the number of new solo drivers grew by almost 13 million from 1990 to 2000. The report also indicates that the number of workers with commutes over 60 minutes grew by 50 percent (!), and that more Americans are leaving for work between 5:00-6:30am.

Pretty hard to cultivate significant friendships when we're spending so much time by ourselves in our cars. Instead, we have more and more people listening to the inanity of talk radio in America. Someone needs to do a study that consider the correlation between increased solo commuting, the explosion of talk radio, and the increased polarization of American "civic" discourse.

Saturday, October 14, 2006

Do Tax Breaks "Establish" Religion?

[Breaking blog silence here. General craziness has kept me from spending much time on Fors Clavigera. What blogging time/energy I've had has gone into The Church and Postmodern Culture blog and Generous Orthodoxy Think Tank.]

The New York Times recently published an interesting series of articles on the ways in which religious organizations receive all kinds of benefits and exemptions from various agencies and arms of the federal government: see "In God's Name," Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

Granted, such policies do not seem to violate the "establishment" clause, since the same benefits are extended to all religions. So the government is clearly not in the business of establishing "a" religion. However, the Part 4 article raises a question that has always nagged me: what about non-religious ("secular") organizations and individuals who sacrificially devote themselves to the common good? Should the pastor of the megachurch in a wealthy Chicago suburb get tax-free housing, while the inner-city teacher who devotes her life to serving the disadvantaged does not? While such policies do not establish "a" religion, they do seem to establish "religion" over non-religious commitments to serve the common good. And it doesn't seem to me that a "liberal" or constitutionally "secular" state has the resources to extend such benefits to religious organizations but not non-religious ones.

The New York Times recently published an interesting series of articles on the ways in which religious organizations receive all kinds of benefits and exemptions from various agencies and arms of the federal government: see "In God's Name," Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4.

Granted, such policies do not seem to violate the "establishment" clause, since the same benefits are extended to all religions. So the government is clearly not in the business of establishing "a" religion. However, the Part 4 article raises a question that has always nagged me: what about non-religious ("secular") organizations and individuals who sacrificially devote themselves to the common good? Should the pastor of the megachurch in a wealthy Chicago suburb get tax-free housing, while the inner-city teacher who devotes her life to serving the disadvantaged does not? While such policies do not establish "a" religion, they do seem to establish "religion" over non-religious commitments to serve the common good. And it doesn't seem to me that a "liberal" or constitutionally "secular" state has the resources to extend such benefits to religious organizations but not non-religious ones.

Saturday, August 05, 2006

Driving Through the Fly-Over States

For the sixth time since 1999, our family is making a cross-country trek to California: 1 minivan, 2 adults, 4 kids, 2200 miles (x2), 3 days, 6 people/hotel room. You do the math.

But there's no better way to see America--indeed, no more "American" way to see America--than to drive it. In particular, I was struck this time how few cultural commentators actually drive through these "fly over" states. We should admit that there's a class element at work here: if you're driving across Nebraska and Wyoming to enjoy time in the Napa Valley, then chances are you can't really afford to be hanging out in the Napa Valley. And so driving across the fly-over states is a bit like riding the city bus: you meet an "interesting" cross-section of people (a massive Harley-Davidson rally in Sturgis, SD filled I-80 with bikes and people of all kinds). But this is just to be reminded that the world is bigger than the comfy, educated confines of the East Coast.

So most of the cultural elites who get to comment on culture spend very little time in these regions of "red" America. Now granted, I can understand why: for instance, in the hotels we stay at (only requirement: free continental breakfast must be included; our family of 6 makes a killing on that :-), even CNN is too liberal, so unlike the airports of the flying class, the lobbies and breakfast nooks of these fly-over hotels blare FOX News at all hours. (I thought I was going to have a coronary when forced into the same room as their coverage of the Israel/Lebanon conflict this morning.) And civil religion is in full swing in these parts, all under the rubric of the "heartland" (why does that call to mind the German Heimat?)--as in the "Heartland Museum of Military Vehicles" in Lexington, NE, or the Wal-mart temples that are found in even the most obscure places out here.

Curious sightings, too: like in central Nebraska, when we whizzed past a huge, hand-painted sign that proclaimed in scrawled letters: "Outlaw Sodomy." Who exactly is the audience for this sign? And what's the impetus? It's not like there's a huge influx of the "creative class" in Gothenberg, NE. A cynical scan of the local demographics had me wondering if maybe this was a sign the local livestock had erected.

But for all that, there's still an inestimable charm about the fly-over states. One finds oneself drawn into long conversations at gas stations and drive-thrus, just because folks are so darn friendly. And for all the critique of the idolatry of "manifest destiny," it was still a bit of a boyhood dream when we visited a Pony Express station in NE, and found in there a gracious, dignified older woman who shared with our kids the story--without too much propaganda--of the shortlived Pony Express.

And, of course, there's the geography: the unbelievable array of colors and curvatures as one moves across the corn states, through the plains, into the desert and up the mountains. And that's just one day! Groves on the edge of tiny lakes in Nebraska seem to be hiding young lovers curled up in the grass or skinny dipping under the trees; at times western Wyoming looks like a lunar landscape, while at other times the Wyoming sky is so vast and sprawling that one thinks it just might be falling.

So I don't consider driving through the fly-over states a drudgery (even if, I confess, I too easily lapse into a kind of East Coast cynicism about middle-American 'culture'--as if somebody from Grand Rapids, MI has any right to be a snob! ;-). Rather, I consider this cross-country ritual both a discipline and a blessing: field research, and an opportunity to be enriched. And I hope this sinks into my kids' blood, so that even if they make it into that "class" which can afford to fly-over this expanse, they'll choose not to--because they'll know what they're missing.

But there's no better way to see America--indeed, no more "American" way to see America--than to drive it. In particular, I was struck this time how few cultural commentators actually drive through these "fly over" states. We should admit that there's a class element at work here: if you're driving across Nebraska and Wyoming to enjoy time in the Napa Valley, then chances are you can't really afford to be hanging out in the Napa Valley. And so driving across the fly-over states is a bit like riding the city bus: you meet an "interesting" cross-section of people (a massive Harley-Davidson rally in Sturgis, SD filled I-80 with bikes and people of all kinds). But this is just to be reminded that the world is bigger than the comfy, educated confines of the East Coast.

So most of the cultural elites who get to comment on culture spend very little time in these regions of "red" America. Now granted, I can understand why: for instance, in the hotels we stay at (only requirement: free continental breakfast must be included; our family of 6 makes a killing on that :-), even CNN is too liberal, so unlike the airports of the flying class, the lobbies and breakfast nooks of these fly-over hotels blare FOX News at all hours. (I thought I was going to have a coronary when forced into the same room as their coverage of the Israel/Lebanon conflict this morning.) And civil religion is in full swing in these parts, all under the rubric of the "heartland" (why does that call to mind the German Heimat?)--as in the "Heartland Museum of Military Vehicles" in Lexington, NE, or the Wal-mart temples that are found in even the most obscure places out here.

Curious sightings, too: like in central Nebraska, when we whizzed past a huge, hand-painted sign that proclaimed in scrawled letters: "Outlaw Sodomy." Who exactly is the audience for this sign? And what's the impetus? It's not like there's a huge influx of the "creative class" in Gothenberg, NE. A cynical scan of the local demographics had me wondering if maybe this was a sign the local livestock had erected.

But for all that, there's still an inestimable charm about the fly-over states. One finds oneself drawn into long conversations at gas stations and drive-thrus, just because folks are so darn friendly. And for all the critique of the idolatry of "manifest destiny," it was still a bit of a boyhood dream when we visited a Pony Express station in NE, and found in there a gracious, dignified older woman who shared with our kids the story--without too much propaganda--of the shortlived Pony Express.

And, of course, there's the geography: the unbelievable array of colors and curvatures as one moves across the corn states, through the plains, into the desert and up the mountains. And that's just one day! Groves on the edge of tiny lakes in Nebraska seem to be hiding young lovers curled up in the grass or skinny dipping under the trees; at times western Wyoming looks like a lunar landscape, while at other times the Wyoming sky is so vast and sprawling that one thinks it just might be falling.

So I don't consider driving through the fly-over states a drudgery (even if, I confess, I too easily lapse into a kind of East Coast cynicism about middle-American 'culture'--as if somebody from Grand Rapids, MI has any right to be a snob! ;-). Rather, I consider this cross-country ritual both a discipline and a blessing: field research, and an opportunity to be enriched. And I hope this sinks into my kids' blood, so that even if they make it into that "class" which can afford to fly-over this expanse, they'll choose not to--because they'll know what they're missing.

Sunday, July 30, 2006

The Sunday Paper in 1984

Fors Clavigera was launched in an Orwellian spirit disappointed, frustrated, and at times frightened by a world too much like that of 1984. While posts along that line have subsided, the external realities have not. Today's local paper carried several articles that confirm the point:

It's precisely things like this that make it not so hard to understand how even some really sharp scholars like David Ray Griffin can be suspicious to the point of arguing for US government involvement in 9/11. See the site of the Muslim-Jewish-Christian Allienace for 9/11 Truth (apparently no savvy web-designers have joined the team), Scholars for 9/11 Truth, and a fairly comprehensive and interesting article from the Chronicle of Higher Education on the phenomenon.

- A New York Times piece noting that the "family values" cynics otherwise known as Republicans in the House passed a bill to raise the minimum wage only because they also tacked on a little proposal to also decrease the estate tax--a change only of interest to the wealthiest echelons of this country. And so these bastards get to say that they voted to raise the minimum wage, all the while knowing the Democrats in the Senate will sink the proposal because of the estate tax addendum. This is shear sophistry, promulgated by Bible-belt conservatives in a move that is so cynical and nihilist that even Nietzsche would blush.

- A nearly week-old AP piece documenting how minimalist Bush protesters--people who simply wore anti-Bush T-shirst to rallies, for instance--were arrested and handcuffed at a number of events, including not just Republican party events, but tax-payer funded public events. (For analysis, rent V for Vendetta, out on DVD on Tuesday.)

- Then in the Opinions section the Grand Rapids Press treated us (as usual) to Michael Ramirez's 7/27/06 cartoon propoganda regarding Israel, while a Reuters headline today document that an Israeli airstrike had killed 60 civilians, including at least 37 children--while the White House gave poor Israel time to work things out (and Beirut promptly let Condi Rice know that she wasn't welcome for tea, sympathy, or a piano concerto).

It's precisely things like this that make it not so hard to understand how even some really sharp scholars like David Ray Griffin can be suspicious to the point of arguing for US government involvement in 9/11. See the site of the Muslim-Jewish-Christian Allienace for 9/11 Truth (apparently no savvy web-designers have joined the team), Scholars for 9/11 Truth, and a fairly comprehensive and interesting article from the Chronicle of Higher Education on the phenomenon.

Monday, July 24, 2006

Conservative Temptations

Frustrations with what passes for the "left" AND "right" in this country have found me re-considering the possibility that I might be a "conservative" (!). Of course this has nothing whatsoever to do with the kabal of free-market revolutionaries who somehow convinced the world that they were conservatives. Rather, I mean a good, old, real conservatism--which flirts with feudalism, aristocracy and English "gentlemen"--not the banalities of the nouveau riche or the oligarchy that passes itself off as democratic.

In this vein, I find myself more and more drawn (not convinced, I'd say, but charitably listening) to someone like Roger Scruton. Thanks to the New Pantagruel for publishing a delightful interview with Scruton, "The Joy of Conservatism."

In this vein, I find myself more and more drawn (not convinced, I'd say, but charitably listening) to someone like Roger Scruton. Thanks to the New Pantagruel for publishing a delightful interview with Scruton, "The Joy of Conservatism."

Tuesday, July 11, 2006

Barack Obama: Another Reason to Leave the Christian Left

First, given what I'll say in a moment, let me state for the record (again!) that I am no fan, supporter or sympathizer of the Religious Right. To the contrary. But there seems to be no shortage of Christian scholars, pundits, and armchair cultural critics pointing out the inadequacies, inconsistencies, and injustices of the Religious Right. Why repeat it here?

Instead, I tend to be more motivated to point out the deficiencies of what passes for the "Religious Left" in this country. ("Left" is clearly a relative term, since I rarely hear the Christian "left" in this country really challenge the mechanisms of capitalist, market economies. Here a Victorian, Christian socialist like F.D. Maurice makes Jim Wallis sound like a PR rep for Wal-Mart. But I digress...) Unfortunately, however, in the bifurcated world we inhabit, if you're not with us, you're against us. So my critique of the Christian Left is too often immediately mistaken as an indicator that I'm a card-carrying member of the Religious Right, or my critique of the Religious Right is (mis)taken as evidence that I'm part of that motley crew which is the Religious Left. Neither is the case. But enough preliminaries...

Granted, Jim Wallis has tended to bear the brunt of my frustrations with the Christian Left--that stems, I suppose, from his visibility, and perhaps even from a kind of attitudinal proximity. Perhaps because I share so many of his concerns and criticisms (let that be noted for the record!), it becomes even more important to highlight the differences--because I think alot is at stake in the differences.

But I'll leave Jim Wallis alone here. Instead, I've been intrigued by the attention garnered by Senator Barack Obama's address to a recent "Call to Renewal" Conference (a Jim Wallis outfit that does alot of good work). [For a summary of news comment, see here.]

What's most disheartening in this is the way that Democrats still consider "religion" instrumentally; that is, they instrumentalize religion insofar as they see it as a strategy for accomplishing a goal. Look at the speech and consider closely just how "religion" is invoked by Obama:

One even sees this instrumentalization of religion in Obama's testimony. He testifies that he was "drawn to the church," to be "in" the church, because of "the power of the African-American religious tradition to spur social change." Now, I certainly believe that justice is an essential aspect of the Gospel, and I believe that being a disciple entails doing justice. But the temptation of the fundamentalism of the left is to make justice an end in itself. It might seem scandalous, but the Gospel is not just--maybe not even primarily--about securing social justice. This is why worship and liturgy and Eucharist play such marginal roles in what the Christian left has to say about "church"--the Left Church is an organization of activists, not a community of worshipers. (This is also why the Left is more comfortable talking about "faith" than "the Church.")

But even if the goal is a good one (like eradicating poverty), if Christian faith is seen as an instrument to another end, then faith is de facto penultimate. And that, I would suggest, is precisely the formula of idolatry--and, in fact, a mirror of the way religion is "used" by the Religious Right (just for different "ends").

Finally, Obama sells the farm when, like Jim Wallis said here at Calvin College, religion must be disciplined by the demands of democracy. Obama puts it this way:

I agree with the opposition to theocracy, and I agree that distinctly religious positions should not be legislated by the state. But what Obama can't seem to imagine is that one might, in fact, pass on the state in order to hold the integrity of what one "knows" on the basis of "religious reasons." I just can't imagine the kind of bifurcated identity that Obama's framework requires--a fractured identity in which, when there is conflict, it is the requirements of "universal" reason which must trump what one knows on the basis of religious faith. From what I can gather, Obama is pro-choice precisely because he doesn't think he can come up with a "universal," rational argument against abortion. (I think it's also because, like almost everyone--Democract and Republican--he's a libertarian at heart.) And so, as a politician, he is pro-choice. If he's going to play by the rules of the pluralist state, and stay within the bounds of the Constitution, he has to set aside his religious beliefs.

But what about another possibility? What about setting aside participation in a state and politics which requires such bifurcation? What about opting out of a democratic rationality which demands ultimate allegiance?

Instead, I tend to be more motivated to point out the deficiencies of what passes for the "Religious Left" in this country. ("Left" is clearly a relative term, since I rarely hear the Christian "left" in this country really challenge the mechanisms of capitalist, market economies. Here a Victorian, Christian socialist like F.D. Maurice makes Jim Wallis sound like a PR rep for Wal-Mart. But I digress...) Unfortunately, however, in the bifurcated world we inhabit, if you're not with us, you're against us. So my critique of the Christian Left is too often immediately mistaken as an indicator that I'm a card-carrying member of the Religious Right, or my critique of the Religious Right is (mis)taken as evidence that I'm part of that motley crew which is the Religious Left. Neither is the case. But enough preliminaries...

Granted, Jim Wallis has tended to bear the brunt of my frustrations with the Christian Left--that stems, I suppose, from his visibility, and perhaps even from a kind of attitudinal proximity. Perhaps because I share so many of his concerns and criticisms (let that be noted for the record!), it becomes even more important to highlight the differences--because I think alot is at stake in the differences.

But I'll leave Jim Wallis alone here. Instead, I've been intrigued by the attention garnered by Senator Barack Obama's address to a recent "Call to Renewal" Conference (a Jim Wallis outfit that does alot of good work). [For a summary of news comment, see here.]

What's most disheartening in this is the way that Democrats still consider "religion" instrumentally; that is, they instrumentalize religion insofar as they see it as a strategy for accomplishing a goal. Look at the speech and consider closely just how "religion" is invoked by Obama:

Now, such strategies of avoidance may work for progressives when our opponent is Alan Keyes. But over the long haul, I think we make a mistake when we fail to acknowledge the power of faith in people's lives -- in the lives of the American people -- and I think it's time that we join a serious debate about how to reconcile faith with our modern, pluralistic democracy.The concern is what will "work." And religion is seen as a way of connecting with the electorate, not as the basis for justice. Progressives need to "get religion" according to Obama so that Democrats can communicate with religious people. But that is a rhetorical, not a religious point. This is confirmed later in Obama's speech when he says:

And that is why that, if we truly hope to speak to people where they're at - to communicate our hopes and values in a way that's relevant to their own - then as progressives, we cannot abandon the field of religious discourse.Even when he later suggests this is "not just rhetorical," the direction of the point is still about how religious discourse will be "effective." (I do agree with Obama's point regarding the false requirements of "secularity.")

One even sees this instrumentalization of religion in Obama's testimony. He testifies that he was "drawn to the church," to be "in" the church, because of "the power of the African-American religious tradition to spur social change." Now, I certainly believe that justice is an essential aspect of the Gospel, and I believe that being a disciple entails doing justice. But the temptation of the fundamentalism of the left is to make justice an end in itself. It might seem scandalous, but the Gospel is not just--maybe not even primarily--about securing social justice. This is why worship and liturgy and Eucharist play such marginal roles in what the Christian left has to say about "church"--the Left Church is an organization of activists, not a community of worshipers. (This is also why the Left is more comfortable talking about "faith" than "the Church.")

But even if the goal is a good one (like eradicating poverty), if Christian faith is seen as an instrument to another end, then faith is de facto penultimate. And that, I would suggest, is precisely the formula of idolatry--and, in fact, a mirror of the way religion is "used" by the Religious Right (just for different "ends").

Finally, Obama sells the farm when, like Jim Wallis said here at Calvin College, religion must be disciplined by the demands of democracy. Obama puts it this way:

Democracy demands that the religiously motivated translate their concerns into universal, rather than religion-specific, values. It requires that their proposals be subject to argument, and amenable to reason. I may be opposed to abortion for religious reasons, but if I seek to pass a law banning the practice, I cannot simply point to the teachings of my church or evoke God's will. I have to explain why abortion violates some principle that is accessible to people of all faiths, including those with no faith at all.I recognize the unique constraints of inhabiting a pluralist state. But Obama opens himself up to a disturbing logic here (and treads on question of faith & reason that are out of his league, I think). With this formulation, Obama creates a kind of "two truths" framework: I can know or be convinced that something is true in (at least) two ways: (1) based on "religious reasons," stemming from revelation, and (2) based on "universal" principles of (just plain) "reason." While I reject the existence of the latter, I'll set that aside here. Let's take Obama's framework: what this means is that while I might believe and know something to be wrong on the basis of "religious reasons," unless I can find a "universal" reason to make the case for that in the "public" sphere, then I cannot expect to legislate the point. I can' expect something to become policy by appealing only to religious reasons.

I agree with the opposition to theocracy, and I agree that distinctly religious positions should not be legislated by the state. But what Obama can't seem to imagine is that one might, in fact, pass on the state in order to hold the integrity of what one "knows" on the basis of "religious reasons." I just can't imagine the kind of bifurcated identity that Obama's framework requires--a fractured identity in which, when there is conflict, it is the requirements of "universal" reason which must trump what one knows on the basis of religious faith. From what I can gather, Obama is pro-choice precisely because he doesn't think he can come up with a "universal," rational argument against abortion. (I think it's also because, like almost everyone--Democract and Republican--he's a libertarian at heart.) And so, as a politician, he is pro-choice. If he's going to play by the rules of the pluralist state, and stay within the bounds of the Constitution, he has to set aside his religious beliefs.

But what about another possibility? What about setting aside participation in a state and politics which requires such bifurcation? What about opting out of a democratic rationality which demands ultimate allegiance?

Saturday, June 24, 2006

Gardens of Delight

West Michiganians take summer pretty seriously. We noticed this when we moved here in June 2002 and found that church life retreats to a kind of summer hibernation. I think I now understand why: After long, cold winters, West Michiganians have only a small window to enjoy their gorgeous beaches, and so pursue summer with reckless abandon.

At the Smith house, what we relish most about summer are the gardens my wife faithfully and

lovingly tends. Indeed, her planting of seeds in the basement in snowy darkness of February and March is a harbinger of a spring that is coming. She (literally) sows in hope, looking forward to the frost giving way so that she can transplant the seedlings into new soil, giving them new space and opportunities--and then patiently, with unparalleled attention, working to coax them into bloom.

lovingly tends. Indeed, her planting of seeds in the basement in snowy darkness of February and March is a harbinger of a spring that is coming. She (literally) sows in hope, looking forward to the frost giving way so that she can transplant the seedlings into new soil, giving them new space and opportunities--and then patiently, with unparalleled attention, working to coax them into bloom.Perennials have their own kind of "hope quotient": after watching fall and winter diminish their life, spring becomes a time of waiting for resurrection. Which will return? Sometimes spring brings its own kind of heartbreak, as a plant hasn't weathered the winter. But most of the time, faith gives way to sight, hope deferred is realized, and a garden teaming with color and surprises bursts forth. It's the little

surprises that are most treasured: like when a clump of stubborn lupines which has never yielded a bloom finally blesses us with a gift of color (though even those green stubborn lupines were a source of delight as we enjoyed the way that the dew and water rolled into a ball in the heart of its leaves). Or when the white and pink mix of some lilies surprises the one who planted them.

surprises that are most treasured: like when a clump of stubborn lupines which has never yielded a bloom finally blesses us with a gift of color (though even those green stubborn lupines were a source of delight as we enjoyed the way that the dew and water rolled into a ball in the heart of its leaves). Or when the white and pink mix of some lilies surprises the one who planted them.Deanna's gardens are, without a doubt, a labor of love: love for beauty, soil, and creation, but also love for us--me and the kids. Deanna blesses us with a sanctuary of floral beauty right here in the neighborhood. And I have a sense that Dee also sees the gardens as a sacramental space--as a conduit for God's love for us, as each leaf and bloom is received as a gift from a God who loves to play and delight and bless. Who could look at the teeming, lush beauty of our gardens and not think about the One who loves enough to "give the increase?" We awake each morning to a kind of horticultural morning office of prayer that channels unspeakable grace into our home.

Perhaps most importantly, Deanna's love and attention to her gardens has taught me something that Norman Wirzba's wonderful forthcoming book, Living the Sabbath, finally named for me: that at the heart of Sabbath is not so much "rest" as delight. Granted, it takes time to enjoy, and so one needs to make time for delight, and so there is an intimate connection between Sabbath rest and the delight it's meant to engender. But the end of

Sabbath, the telos of such rest, is delight in God's many gifts--which is why Sabbath is not (just) about a day of the week, but rather a habit of being-in-the-world, a Monday-Friday way of life that knows how to, well, stop and smell the roses. Deanna's day begins with a sort of dutiful prayer walk, beginning with the back gardens--looking for new shoots and leaves and blooms, mourning losses, lamenting the effects of predators--then culminating with coffee on the front porch, taking delight in a new morning glory flower snaking its way up the front railing, or the explosion of orange lilies, or the towering growth of a hunted-for larkspur. I've learned to enjoy this "morning office" like no other, and learn with Deanna to find in our gardens a sacrament of God's love. And I love her for that.

Sabbath, the telos of such rest, is delight in God's many gifts--which is why Sabbath is not (just) about a day of the week, but rather a habit of being-in-the-world, a Monday-Friday way of life that knows how to, well, stop and smell the roses. Deanna's day begins with a sort of dutiful prayer walk, beginning with the back gardens--looking for new shoots and leaves and blooms, mourning losses, lamenting the effects of predators--then culminating with coffee on the front porch, taking delight in a new morning glory flower snaking its way up the front railing, or the explosion of orange lilies, or the towering growth of a hunted-for larkspur. I've learned to enjoy this "morning office" like no other, and learn with Deanna to find in our gardens a sacrament of God's love. And I love her for that.

Thursday, June 22, 2006

Border Patrols and Academic Freedom

As a non-resident alien academic working in the United States, the steady trickle of stories about the State Department and/or Department of Homeland Security denying foreign scholars entrance to the US has some added interest for me. Add to the stories of Tariq Ali and others the newest case, that of Greek political theorist John Milios, who was denied entrace to the States where he was headed to participate in a conference at SUNY Stony Brook (the conference, ironically, was on "How Class Works"). According to the report in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Milios landed at JFK, was told his visa had been revoked--with no explanation of why it had been revoked, and no evidence offered--then interviewed for several hours before being put on a plane back to Greek. The report continues:

In addition to the general McCarthy-like feel of all this (if you haven't seen Good Night and Good Luck, rent it tonight), one of the conference organizers rightly notes the serious academic consequences of this kind of ideological border patrol: isolation.

In the telephone interview on Wednesday, Mr. Milios said that after the attention given the expulsion in Greece, he was called to the U.S. Consulate for an hourlong discussion with a consular official. "It was a friendly talk," he said, "but again it was mainly about my political affiliations."Milios has been a member of the Greek parliament, and is affiliated with the communist party in Greece (like a host of intellectuals around the world, it should be noted).

In addition to the general McCarthy-like feel of all this (if you haven't seen Good Night and Good Luck, rent it tonight), one of the conference organizers rightly notes the serious academic consequences of this kind of ideological border patrol: isolation.

Michael Zweig, director of Stony Brook's Center for Study of Working Class Life, said in a written statement that Mr. Milios's absence "was a serious loss to the intellectual life of the conference and the university."Interesting, in the latest issue of New Blackfriars, British Dominican theologian Fergus Kerr also laments the experience of trying to get into the United States. As he wryly notes:

"The action of U.S. officials on June 8," he said, "isolated American faculty and students from important research results derived overseas and made it impossible for a senior international expert to interact with his colleagues in the United States."

"Having a visa, as it says on the document, is no guarantee that you will be allowed through passport control. That remains, as it says, entirely up to the individual US immigration man or woman at the desk whether to let you in. They seldom look you in the eye, they turn the pages of your passport suspiciously, and you need a ready answer if they snap out at you 'What's your business, sir, in the United States?'— 8 or 9 hours non stop in cattle class probably makes you look witless enough to have been on the wrong flight.American academic colleagues have the luxury of being able to wear their anti-Americanism on their sleeves. Those of us who know what it's like to deal with the INS tread more carefully.

Take care, we are all paying a cost. Think twice about going at all."

Friday, May 12, 2006

"Sometimes there's so much beauty in the world"

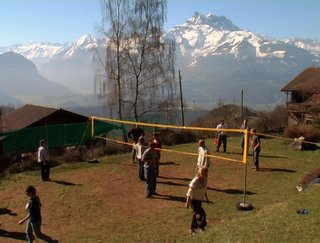

I just got back from my stroll up the mountain to Villars-- perhaps one of the most enjoyable things I've ever done. Trying to put it into words reminds me of negative theology and the utter inadequacy of language.

I just got back from my stroll up the mountain to Villars-- perhaps one of the most enjoyable things I've ever done. Trying to put it into words reminds me of negative theology and the utter inadequacy of language.The path from L'abri begins wending through a hillside meadow that spills out into the sprawling valley below, pinched between the towering heights of the alps. It then dives into the forest, crunching past trickling streams everywhere. Indeed, the whole mountainside was bubbling with water as the mountaintop snow gives way to spring and looks for the best path down to the valley. The trickling streams eventually give way to a teeming springtime flow closer to Villars. The soundtrack for the trek included birdsongs I've not heard before as well as the gentle clanging of a lone cow grazing.

I stopped at the Coop in Villars for my prey: as much Swiss chocolate as my suitcase can carry, as well as Smarties for the kids. (Not those icky American sugar tablets, but rather the real deal we enjoy in Canada.) Not all of the chocolate will make it to my suitcase: On the way back down the mountain, I stopped at a bench on the trail and enjoyed half a bar, sitting under a pine tree, with the sun stealing through in spots, and the snowcapped mountains continuing to impose themselves through the branches. (If I had a corkscrew, I don't think the wine I bought would have made it down the hill either.)

The whole experience reminded me of some Ricky Fitts confessed in American Beauty: "Sometimes there's so much beauty in the world, I feel like my heart is going to cave in." Grace à Dieu.

Postcard from Switzerland

I'm in the midst of enjoying a wonderful week of activity in Switzerland. The week began with my participation in the "Prophets, Priests, and Theologians" conference hosted by the good folks from the Shema Community in Geneva, and co-sponsored by Emergent-UK. The conversation--a nice, pretty intimate gathering of about 50 practitioners (with a few academics)--took place in the Auditoire au Calvin, John Calvin's teaching base in Geneva. Panelists included Brian McLaren, Jason Clark, Andrew Jones, Pete Rollins, myself and a few others. Good people, with good questions, and fun to be with. I'm looking forward to continuing the conversation. It was a special treat for all of us to stay together at night at a wonderful retreat home (next door to a 12-century priory) in Paillonex, France. This added a sense of intentional community to the conference, which helped solidify relationships so that the conversations were charitable and took place in a "safe" environment. A wonderful model.

I'm in the midst of enjoying a wonderful week of activity in Switzerland. The week began with my participation in the "Prophets, Priests, and Theologians" conference hosted by the good folks from the Shema Community in Geneva, and co-sponsored by Emergent-UK. The conversation--a nice, pretty intimate gathering of about 50 practitioners (with a few academics)--took place in the Auditoire au Calvin, John Calvin's teaching base in Geneva. Panelists included Brian McLaren, Jason Clark, Andrew Jones, Pete Rollins, myself and a few others. Good people, with good questions, and fun to be with. I'm looking forward to continuing the conversation. It was a special treat for all of us to stay together at night at a wonderful retreat home (next door to a 12-century priory) in Paillonex, France. This added a sense of intentional community to the conference, which helped solidify relationships so that the conversations were charitable and took place in a "safe" environment. A wonderful model.I then

took the train from Geneva and am now enjoying a stay at L'abri in the little village of Huemoz. L'abri is a community founded by Francis and Edith Schaeffer for those looking to explore questions of faith, particularly in engagement with contemporary culture. Deanna and I were here back in 2003 when I delivered the lectures that have now become Who's Afraid of Postmodernism? (So it was a treat to bring copies of the book here for the L'abri library, in thanks for their hospitality.) I presented two lectures based on the new book I'm working on, tentatively called Desiring the Kingdom. Last night I enjoyed Richard and Karen Bradford's delicious fondue, and today I'm going to hike up to Villars before enjoying a formal lunch discussion with students this afternoon. It's a treat waking up to the Alps in my window--I only wish Dee and the kids were here with me to enjoy it.

took the train from Geneva and am now enjoying a stay at L'abri in the little village of Huemoz. L'abri is a community founded by Francis and Edith Schaeffer for those looking to explore questions of faith, particularly in engagement with contemporary culture. Deanna and I were here back in 2003 when I delivered the lectures that have now become Who's Afraid of Postmodernism? (So it was a treat to bring copies of the book here for the L'abri library, in thanks for their hospitality.) I presented two lectures based on the new book I'm working on, tentatively called Desiring the Kingdom. Last night I enjoyed Richard and Karen Bradford's delicious fondue, and today I'm going to hike up to Villars before enjoying a formal lunch discussion with students this afternoon. It's a treat waking up to the Alps in my window--I only wish Dee and the kids were here with me to enjoy it.

Tuesday, May 02, 2006

Grade Avoidance Behavior: Colbert on Bush

OK, this is surely a sign of my lack of will to really dive into the stack of papers I have to grade. But if you, too, are looking for a way to be slothful, treat yourself to Stephen Colbert's "roast" of George W. Bush at the White House Correspondents Dinner.

Friday, April 28, 2006

Remembering Azusa Street: Pentecostal Centenary

Krista Tippett and the good folks at Speaking of Faith have put together an excellent program on the Azusa Street revival, featuring the wisdom Mel Robeck, whose new book on the Azusa Street revival I've been enjoying since the Society for Pentecostal Studies conference back in March.

Along with the program (which can be listened to online or downloaded as a podcast), the SoF site includes a wealth of resources related to global Pentecostalism. Great stuff.

Along with the program (which can be listened to online or downloaded as a podcast), the SoF site includes a wealth of resources related to global Pentecostalism. Great stuff.

Sunday, April 23, 2006

Kuyper and DeVos: If this is "transformation"...

My recent piece on Neocalvinism in Comment received some criticism either because (1) I suggested links between what now passes for Neocalvinism and the right-wing, libertarian elements of the Republican party, or (2) because I think that's a bad thing.

In that light, I find two recent local events almost laughable--if they weren't also disheartening. First, just a few days ago it was announced that what was formerly "Reformed Bible College" would henceforth be known as Kuyper College. Two days later it was announced that the very first commencement speaker for Kuyper College would be none other than Richard DeVos--co-founder of Amway (now Alticor), author of Compassionate Capitalism, and all-around symbol of the so-called "Reformed" tradition's baptism of Republican libertarian economics and war-mongering foreign policy.

Every square inch?

In that light, I find two recent local events almost laughable--if they weren't also disheartening. First, just a few days ago it was announced that what was formerly "Reformed Bible College" would henceforth be known as Kuyper College. Two days later it was announced that the very first commencement speaker for Kuyper College would be none other than Richard DeVos--co-founder of Amway (now Alticor), author of Compassionate Capitalism, and all-around symbol of the so-called "Reformed" tradition's baptism of Republican libertarian economics and war-mongering foreign policy.

Every square inch?

Thursday, April 13, 2006

Is there a box marked "other?"

My recent article on Neocalvinism in Comment generated some curious comments and reaction (both at the site and via email). Most of it is not worth a reply, but I continue to be amazed by a lack of imagination on the right which thinks that a criticism of the Bush administration can only mean that someone loves all things Clintonian and Democratic. In other words, they seem to imagine that someone who criticizes “the Right” must be a card-carrying member of “the Left” (as if there was one). One would hope for a little more nuance. So I was surprised to see myself being dismissed as yet another “liberal.” I think I’ve pretty clearly indicated—in my critique of Jim Wallis and in my sympathy for Hitchens’ lambasting of the Clintons—that I’m no friend of the left. Instead, I find myself in deep sympathy with Ruskin who, in the very first letter of Fors Clavigera, trying to subvert such simplistic dichotomies:

“Consider, for instance, the ridiculousness of the division of parties into ‘Liberal’ and ‘Conservative.’ There is no opposition whatever between these two kinds of men. There is opposition between Liberals and Illiberals; that is to say, between people who desire liberty, and who dislike it. I am a violent Illiberal; but it does not follow that I must be a Conservative.”

Wednesday, March 15, 2006

The EQ Test: How Evangelical Are You?

I've always secretly enjoyed a genre of humorous, "takes-one-to-know-one," accounts of evangelical Christianity, such as Patricia Klein's Just As We Were, or Sweeney's memoir, Born Again and Again: Surprising Gifts of a Fundamentalist Childhood. So I'm intrigued by the new offering from Joel Kilpatrick's A Field Guide to Evangelicals and Their Habitat. Kilpatrick's is a slight departure from the genre, it seems, insofar as the book is written more for "outsiders," but it clearly displays "insider" knowledge. But this is also a departure insofar as it's less charitable than Klein or Sweeney: the tone seems to be more along the line of The Simpsons' Guide to Evangelicalism. Nevertheless, sure to be entertaining.

For a taste, visit the "EQ Test" on the book's website, designed to help you discern "how evangelical" you are. Classic cases of evangelical shibboleths.

For a taste, visit the "EQ Test" on the book's website, designed to help you discern "how evangelical" you are. Classic cases of evangelical shibboleths.

Friday, March 10, 2006

Bush and Blair's Secular Religion

Philip Blond and Adrian Pabst, two bright young British theologians, today published an insightful commentary on "The Twisted Religion of Blair and Bush" in the International Herald Tribune (roughly an arm of the NYT in Europe, for those not familiar). A fine example of thoughtful, accessible theologically-informed public commentary.

Friday, March 03, 2006

I'm Not Kidding

Left Behind: The Video Game

Yet one more piece of evidence confirming the Babylonian captivity of American evangelicalism.

Yet one more piece of evidence confirming the Babylonian captivity of American evangelicalism.

Sunday, February 12, 2006

Evangelicals and Climate: Update

The Evangelical Climate Initiative can now be found online (including in .pdf), including the list of signatories. I was very encouraged to see that the President of my home institution signed on. The list of signatories is worth a look. Let's hope this might be the beginning of an erosion of the Colorado Springs consensus.

Wednesday, February 08, 2006

Evangelical Cliimate Initiative

I had been pretty disheartened last Saturday by Washington Post story noting that the National Association of Evangelicals would not issue a statement regarding global warming ("climate change" in newspeak). The NAE's initiative on this was basically derailed by the usual unholy trinity of James Dobson, Chuck Colson, and Richard Land (Al Moehler must have been unavailable for comment).

However, today some more encouraging news: the NYT reports on a 'renegade' group of evangelicals issuing a statement on their own. Unfortunately I've not yet been able to locate a copy of the "Evangelical Climate Initiative," but I'm eager to see the list of endorsers.

[Posting this from a fabulous visit to Seattle, lecturing at Northwest University. Deanna has been able to make the trip with me due to the support of wonderful friends. Today we head up to Vancouver for some more lectures at Regent College.]

However, today some more encouraging news: the NYT reports on a 'renegade' group of evangelicals issuing a statement on their own. Unfortunately I've not yet been able to locate a copy of the "Evangelical Climate Initiative," but I'm eager to see the list of endorsers.

[Posting this from a fabulous visit to Seattle, lecturing at Northwest University. Deanna has been able to make the trip with me due to the support of wonderful friends. Today we head up to Vancouver for some more lectures at Regent College.]

Wednesday, January 25, 2006

God is Love: Benedict XVI's First Encyclical

The New York Times is, unsurprisingly, "surprised" that Benedict XVI's first encyclical (Deus caritas est) would be concerned with love. Their surprise is due to the fact that they'd bought the story of Ratzinger the Inquisitor rather than engaging the history of his work.

I've not yet had a chance to read the encyclical closely (assigning it in my "Urban Altruism" seminar this spring will provide an opportunity), but a quick skim indicates that what's really at stake here are questions about the relationship between church and "state," and just which entity is responsible for the formation of a "just" society. (That a discussion of love would entail a discussion of justice is the sort of link that liberalism couldn't think.) In this regard, Benedict follows a pretty straightforward line regarding subsidiarity--a line which, I think, could be justly questioned. Nevertheless, this is an important document that the entire global church--and even states--ought to engage. One could hope it will stimulate important conversations on these matters.

I've not yet had a chance to read the encyclical closely (assigning it in my "Urban Altruism" seminar this spring will provide an opportunity), but a quick skim indicates that what's really at stake here are questions about the relationship between church and "state," and just which entity is responsible for the formation of a "just" society. (That a discussion of love would entail a discussion of justice is the sort of link that liberalism couldn't think.) In this regard, Benedict follows a pretty straightforward line regarding subsidiarity--a line which, I think, could be justly questioned. Nevertheless, this is an important document that the entire global church--and even states--ought to engage. One could hope it will stimulate important conversations on these matters.

Monday, January 23, 2006

Canadian Election Today

You wouldn't know it from most mainstream American media coverage (the BBC highlights it more), but today Canadians go to the polls in a federal parliamentary election. The Globe & Mail is projecting a minority government for the Conservative Party. The challenge for the conservatives is finding anyone to play coalition government with. This could be a very short-lived government.

It's at least interesting to note that as Latin American elections have quite steadily swung to the left, North American electorates are swinging to the right (though the "right" in Canada still makes American Democrats look like Thatcherites on some issues). However, there is an interesting subplot to this Canadian election, too, as the NDP seem to be gaining ground (as well as the Bloc Quebecois, which is also left-of-center). We'll see...

It's at least interesting to note that as Latin American elections have quite steadily swung to the left, North American electorates are swinging to the right (though the "right" in Canada still makes American Democrats look like Thatcherites on some issues). However, there is an interesting subplot to this Canadian election, too, as the NDP seem to be gaining ground (as well as the Bloc Quebecois, which is also left-of-center). We'll see...

Monday, January 16, 2006

Christian Scholars, Public Intellectuals, and the Challenges of Finitude

I’ve found myself bumping up against my finitude quite a lot in the past month, which has got me to thinking some about the unique challenges for Christian scholars who want to also try to play the role of public intellectuals. (Gideon Strauss’s recent Comment article on the New York intellectuals furthered my thinking on this score.)

Perhaps some prefatory words about “public intellectuals” are in order. By a “public intellectual,” I mean someone who brings critical, analytic, and synthetic theoretical skills to bear on issues of public concern—and then is able to articulate and express both a critique and vision in ways that are provocative, winsome, insightful, and—one hopes—persuasive. Many public intellectuals are credentialed scholars who feel impelled—as a matter of public trust—to take their skills and expertise outside the narrow (but legitimate) discussions of the academy. (A host of examples here, but a few that come to mind: Cornel West, Noam Chomsky, Richard Dawkins—not to mention a whole host of French thinkers from Sartre to Derrida to Luc Ferry.) But two provisos are in order here: First, not all scholars are, or are called to be, public intellectuals. And I don’t mean to suggest that scholars who stay within the confines of academic discourse are somehow failing in their vocation. The world of scholarly investigation and conversation is a legitimate end in itself and need not be justified only by “application” to public issues. That would be to fall into the worst sort of pragmatism. Second, not all public intellectuals are (or need be) credentialed scholars. Someone like Christopher Hitchens immediately comes to mind. A brilliant, critical mind emerging from Oxford, Hitchens does not have a PhD. But that hardly undercuts his ability to fulfill the role I’ve sketched above.

Now, with that in mind, I think there is a unique set of challenges for the Christian scholar who would seek to be a public intellectual. Let me enumerate just three as a start:

1. The Christian scholar who senses a vocation as a public intellectual immediately runs up against a challenge that I would think does not confront a “secular” public intellectual: guilt. Perhaps this is the result of my Calvinism working overtime, but I think it is a phenomenon that was glimpsed powerfully by Augustine in Book X of the Confessions. I need to ask myself just why I want to be a public intellectual. Is it just for the (relative) “fame?” Augustine’s reflection on this challenge is, for me, one of the most haunting passages of the Confessions. Extending his reflection on the temptations outlined in 1 John 2:16 (the lust of the flesh, the lust of the eyes, and worldly ambition), Augustine lands on the third as the one that continues to plague him most: “Surely the third kind of temptation has not ceased to trouble me, nor during the whole of this life can it cease. The temptation is to wish to be feared or loved by people for no reason other than the joy derived from such power.” (Conf. 10.36.59). In fact, upon becoming a bishop, the temptation only increased such that Augustine the bishop could confess: “This is [not “was”] the main cause why I fail to love you.” And I have to confess the same.

And so, unlike other public intellectuals who aren’t beset by this Augustinian self-suspicion, the Christian who would become a public intellectual and who is really honest with himself or herself must run up against this kind of lust for fame operative in one’s soul. That first whiff of public acclaim is an intoxicating drug. But Augustine also recognizes the complexity and messiness of all this, for he clearly counsels that the solution is not a withdrawal from acting for the public good. For indeed, even the one acting as a public intellectual (and surely a bishop was a public intellectual) with the purest of motives will nevertheless find himself the subject of praise and acclamation. Should Augustine abandon doing his public labors well just so that he’s not tempted by fame and the praise of men? By no means, he concludes. This would be akin to think the way to avoid gluttony is to avoid eating. Rather, the good work of a public intellectual should be accompanied by a rigorous self-examination—and real honesty about how easy it is to get hooked on the drug of “public interest.”