It is an absolute honor and delight for me to have been recently appointed as Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Divinity at Trinity College, University of Toronto (and not just because Trinity is the fabled inspiration for The College of St. John & the Holy Ghost in Robertson Davies' novel, Rebel Angels!).

It is an absolute honor and delight for me to have been recently appointed as Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Divinity at Trinity College, University of Toronto (and not just because Trinity is the fabled inspiration for The College of St. John & the Holy Ghost in Robertson Davies' novel, Rebel Angels!). Friday, January 20, 2012

"Radical Orthodoxy and Political Theology": Grad Course @ Trinity College

It is an absolute honor and delight for me to have been recently appointed as Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Divinity at Trinity College, University of Toronto (and not just because Trinity is the fabled inspiration for The College of St. John & the Holy Ghost in Robertson Davies' novel, Rebel Angels!).

It is an absolute honor and delight for me to have been recently appointed as Visiting Professor in the Faculty of Divinity at Trinity College, University of Toronto (and not just because Trinity is the fabled inspiration for The College of St. John & the Holy Ghost in Robertson Davies' novel, Rebel Angels!). Thursday, January 12, 2012

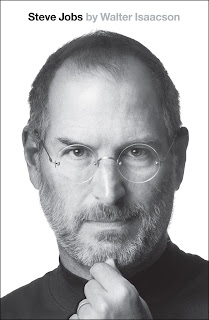

Constrained to be Free: On "Freedom" Software

Is this what it's come to? Smart, creative adults needs to pay for software to save themselves from distraction by the internet? Apparently.

Is this what it's come to? Smart, creative adults needs to pay for software to save themselves from distraction by the internet? Apparently.Freedom is a simple productivity application that locks you away from the internet on Mac or Windows computers for up to eight hours at a time. Freedom frees you from distractions, allowing you time to write, analyze, code, or create. At the end of your offline period, Freedom allows you back on the internet. You can download Freedom immediately for 10 dollars, and a free trial is available.

Wednesday, January 11, 2012

Adele as Allegory

Tuesday, January 10, 2012

@C3Nashville Conference, March 1-3, 2012

I'll be joining a great line up folks for the upcoming C3 (Christ, Church, Culture) Conference hosted by the St. George's Institute in Nashville, TN on March 1-3, 2012. This conference has quickly built a strong reputation for bringing together people at the intersection of theology, ministry, the arts, and cultural engagement. I'll be joining other plenary speakers such as Kenda Creasy Dean, Makoto Fujimura, Andy Crouch, and George Carey. There are also a number of breakout workshops (I'll lead one). And it all kicks off with a tapas reception--what's not to love?

I'll be joining a great line up folks for the upcoming C3 (Christ, Church, Culture) Conference hosted by the St. George's Institute in Nashville, TN on March 1-3, 2012. This conference has quickly built a strong reputation for bringing together people at the intersection of theology, ministry, the arts, and cultural engagement. I'll be joining other plenary speakers such as Kenda Creasy Dean, Makoto Fujimura, Andy Crouch, and George Carey. There are also a number of breakout workshops (I'll lead one). And it all kicks off with a tapas reception--what's not to love?Monday, January 09, 2012

Favorite Reads 2011: Novels

4. Richard Price, Kate Vaiden.

4. Richard Price, Kate Vaiden.

Oh but Lyndsey Farel, she was Sandra's pal. People wanted to f**l off her too but she did not let them. I was down at the shops and saw her. She was looking at me. I thought she was. Another boy was there and we were smoking a fag. She had black hair coming down both sides of her eyes, and her skirt and her legs just like the way she walked and then how she turned round and just how her skirt stuck out, and just swinging. Some lasses' skirts just done that and it looked good just how it went, I thought it was good.

A bench was there and I sat on it. It was funny how it was just me and I was at the Sunday School and nobody else was. Out of everybody that was all my age only it was me. How come? It was just a thing and I was thinking about it. Then all other stuff. And a secret wee thing how really if I was a Pape. That was a wee thing I used to think. If I was one and did not know it so I was not going to Chapel but just to Church. I should have been going to Chapel but was not. Because I did not know. Because nobody told me. If I did not know. So I could not do it.

Saturday, January 07, 2012

Favorite Reads 2011: Nonfiction

5. Val Ross, Robertson Davies: A Portrait in Mosaic.

5. Val Ross, Robertson Davies: A Portrait in Mosaic. Val Ross' quasi-biography employs the same method as Nelson Aldrich's potrait of George Plimpton in George, Being George: George Plimpton's Life as Told, Admired, Deplored, and Envied by More Than 300 Friends, Relatives, Lovers, Acquaintances, Rivals--and a Few Unappreciative ...--which I reviewed a few years ago (seehttp://jameskasmith.blogspot.com/2009/02... ). The strategy is to compile snippets of conversations and testimonies from a wide array of family, friends, and acquaintances, organized into a chronological survey of a life. It is perhaps the ideal way for a journalist to write a sort of biography, and Ross undertook herculean labor in tracking down sources. (Sadly, Ross died of cancer before this book was published.)

The result is a deceptively easy read that breezes through Davies life, yet with a rich cumulative effect. I'm now picking up The Manticore.

In civilization men are taken at their own valuation because there are so many ways of concealment, and there is so little time, perhaps even so little understanding. Not so down South. These two men went through the Winter Journey and lived: later they went through the Polar Journey and died. They were gold, pure, shining, unalloyed. Words cannot express how good their companionship was.Through all these days, and those which were to follow, the worst I suppose in their dark severity that men have ever come through alive, no single hasty or angry word passed their lips. When, later, we were sure, so far as we can be sure of anything, that we must die, they were cheerful, and so far as I can judge their songs and cheery words were quite unforced. Nor were they ever flurried, though always as quick as the conditions would allow in moments of emergency. It is hard that often such men must go first when others far less worthy remain. [...]I am not going to pretend that this was anything but a ghastly journey, made bearable and even pleasant to look back upon by the qualities of my two companions who have gone.

Which are you? Are you a Captain Scott, tense, anxious, man-hauling your way through the snow by main force yet describing it brilliantly afterwards, relying for your authority on military rank and charm? Are you a Shackleton, with exactly the same prejudice against dog-sledging as Scott, having learned it with him on the same disastrous journey in 1902, but allied to a wonderfully supple gift for managing people, maternally kind when you could be, unhesitatingly ruthless when you had to be? Are you Amundsen, driven, impeccably self-educated in polar technique, yet far more of a polar performance artist than a word man, and so best appreciated ever after by skiers, mountaineers, ice athletes who can dance through the same moves he made, on his way to the Pole in 1912? Are you, far more obscurely, a Shirase, scarcely noticed by the main contenders for the Pole when he turned up in the Ross Sea in 1912, yet determined to be there, to make a start?

Friday, January 06, 2012

Epiphanies: Favorite Poems and Poets, 2011

Today, Ephiphany, is a fitting day to briefly highlight the poets I spent some time with in 2011, since I'll begin with a poem on just that.

Today, Ephiphany, is a fitting day to briefly highlight the poets I spent some time with in 2011, since I'll begin with a poem on just that.EpiphanyA momentary rupture to the vision:the wavering limbs of a birch fashionthe fluttering hem of the deity’s garment,the cooling cup of coffee the ocean the deitywaltzes across. This is enough—but sometimesthe deity’s heady ta-da coaxes the cherriesin our mental slot machine to line up, andour brains summon flickering silver likesalmon spawning a river; the jury decidesin our favor, and we’re free to see, for now.A flaw swells from the facets of a day, increasingthe day’s value; a freakish postage stamp mailsour envelope outside time; hairy, claw-likemagnolia buds bloom from bare branches;and the deity pops up again like a girl froma giant cake. O deity: you transfixing transgressor,translating back and forth on the borderwithout a passport. Fleeing revolutionsof same-old simultaneous boredom andboredom, we hoard epiphanies under the bed,stuff them in jars and bury them in the backyard;we cram our closet with sunrise; prop up our feetand drink gallons of wow!; we visit the doctorbecause all this is raising the blood’s levels ofc6H3(OH)2CHOHCH2NHCH3, the heart caughtin the deity’s hem and haw, the oh unfurlingfrom our chest like a bee from our cup of coffee,an autochthonous greeting: there. Who saw it?

Wednesday, January 04, 2012

The Kids Are Not All Right (cross-posting)

Do me a favor: Promise me you'll read this post with The National's "Conversation 16" video playing in the background. Don't try to exegete the lyrics, just let it rattle and hum a couple of times through. If you're looking for a more adventuresome video version, try this (advanced warning: zombie ahead!).

The kids are not all right. That is the evidence-based, data-driven picture that is emerging from sociologist Christian Smith's National Study of Youth and Religion. His account of the paucity of moral reasoning among twentysomethings can't be chalked up as mere grumpy-old-man harumphing about "those damn kids" or a reactionary conservative harangue about godless "secular" America. Smith's longitudinal study provides a deeply worrisome snapshot of the state of spiritual maturity and moral reflection among millenials. Indded, I found the first chapter of his latest book, Lost in Transition: The Dark Side of Emerging Adulthood, to be positively harrowing in its account of how these young people are "morally adrift." But as Smith is at pains to emphasize: the point isn't to demonize twentysomethings; the point is for the rest of us to look in the mirror and ask ourselves how we produced this generation.

Earlier volumes (Soul Searching and Souls in Transition) did the same with respect to religious understanding and spiritual maturity. While the study considers young people from various religions and those without any, the implications for Christian ministry were especially challenging (explored with verve and wisdom by Kenda Creasy Dean in Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teens is Telling the Church). The "faith" that young Christians were learning (often from age-segmented youth ministries) was not trinitarian Christian faith but rather "moralistic therapuetic deism": a strange deity who embraces antimonies and paradox, who is both a legalist and a great big bubble gum machine in the sky--the perfect god for American civil religion, who judges premarital sex but is enough of a big teddy bear to also let it slide, because really, he just wants you to be happy. The god of moralistic therapeutic deism is a lot like Oprah, it turns out.

And if that's the god that our young people worship, we need to ask ourselves: What have we done? As Dean puts it, this is an indictment of the church, not teenagers.

This is why I think Bert Polman's upcoming seminar (June 18-22, 2012), "Singing What We Believe: Theology & Hymn Texts," is such an excellent, timely opportunity for a blend of scholars and practitioners to spend some time together thinking about these issues. For maybe it's at least partly the case that young people have been sung into the moralistic therapeutic deistic faith. Here's a description of the seminar:

Congregational songs have often been called the lay persons’ “handbook of theology” as “psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs” have a unique mix of doxa (worship) and logia (teaching) which shape and express the life of Christians. This seminar will explore initially the theology of hymn texts, based on an analysis of some 250 classic hymn lyrics and a similar number of contemporary Praise-Worship texts. Then the seminar participants will discuss the relationship between the theological themes of such texts and the prevalence of what sociologists of religion (Christian Smith, et al) have termed “moralistic therapeutic deism.” In other words, this interdisciplinary seminar will focus not only on doxa and logia but also onpraxis, and is expected to raise issues about current religious convictions and practices of Christians.

Do consider applying (by February 1)!

Monday, January 02, 2012

Favorite Reads 2011: Short Stories

Twas the year of New Yorker stories for me, I guess. While I dabbled in some other collections (Hemmingway, Alice Munro), here are the five stories that made a dent on my imagination this past year (all published in the New Yorker):

Twas the year of New Yorker stories for me, I guess. While I dabbled in some other collections (Hemmingway, Alice Munro), here are the five stories that made a dent on my imagination this past year (all published in the New Yorker):The shock of it. He, Ravitch, who had always thought his mind inviolable, had naively conceived of depression as merely a state of being very sad. The trembling of his hands and the motor roaring in the back of his skull had enlightened him. Clinical depression, a succession of doctors had explained gravely, patiently, defining his suffering. Not uncommon under the circumstances. Not severe enough for hospitalization. A cocktail of various pills, taken over three months, had rid him of the worst symptoms. Time and new habits would undoubtedly assuage his nocturnal agitation. What was left was simply the feeling of being scooped out, hollow. No other words for it. But what did it portend?

Sunday, January 01, 2012

Favorite Reads 2011: Theology for Christian Scholars

Hans Boersma, Heavenly Participation: The Weaving of a Sacramental Tapestry (Eerdmans, 2011).

Hans Boersma, Heavenly Participation: The Weaving of a Sacramental Tapestry (Eerdmans, 2011).  N.T. Wright, Scripture and the Authority of God: How to Read the Bible Today (HarperOne, 2011).

N.T. Wright, Scripture and the Authority of God: How to Read the Bible Today (HarperOne, 2011).